But It’s Mine!: An Illustrator’s Brief Guide to Selling Out

“No illustrator has a ‘style’ until they literally can’t do anything else,” is something a professor once told myself and my fellow BFA-seeking illustration cohort. While I have gone back-and-forth with whether I agree with this statement, one thing is clear between the lines: one’s style is sacred. As a young illustrator in my early twenties, I fell deeply into this mentality.

High Hopes, High Tuitions, High Horses

Art school is an interesting place, where everyone is special and egos are constantly assembled and dismantled by peers and faculty on a near-daily basis. Between in-class critiques and student shows, smoker circles and computer lab buddies, there is a deep, dark well of feedback layered in piles of jealousy. In my anecdotal opinion, one’s “style” acts as the ego’s ladder that allows the id to climb up from the bottom of the psyche and freak everyone out from the top of the brain iceberg. And artists don’t seem to bother with that superego nonsense.

Art school attracts and instills strong personalities. Self-righteously principled and stubborn, my ilk not only lean on style, but also personal virtues. This presents a massive problem as art school is NOT cheap. The values of many artists lie comfortably in the realm of anti-consumerism, anti-capitalism and anti-commodification. This ultimately leads to being unintentionally anti-making-enough-money-to-pay-off-those-student-loans.

Take This Job and Draw It

So, here we see a problem. Being a professional illustrator intrinsically entails selling work. While almost every one of us wants to simply produce whatever work we want and live like sultans off the sales, that is a reality for only a select few. The rest of us will spend our lives hocking client work to keep Sallie Mae off our asses and food on our ink-stained tables. Now, we see where our sacred notion of “style” needs to be lifted off the ego-encrusted shrine in the basement of our souls and commodified for private commission.

Back to me for a second, I’ll tell you that my first full-time job away from dear mother art school was in fact not an illustration job, but a graphic design job. It was a terrible company with a terrible owner and terrible internal values. From day one, my self-righteous, punk rock red flags were popping up like whack-a-moles, all screaming, “This company is everything you hate!”

I was just as under-qualified for the job as I was cheap. Having fairly limited coursework in design, I farted my way through best I could, brimming with impostor syndrome and seething through every unethical day I spent working there. Every virtue-breaking step I took, I still managed to create work for which I felt something that was not entirely unlike pride. Then, it happened: “Hey, Frank. Can we get a couple illustrations for this [some kind of ad thing],” and my heart dropped.

How could I release this part of me to this evil empire of greed and microwave fish smell?! (I just want to throw this out there: One dude I worked with cooked salmon in the microwave almost every day. Yeah.) As I trundled on doing passionless design work for emails and print ads, I burned out every last shred of humanity from these illustrations I produced. I mean, they were, like, BLEAK. I put my “style” back into its brain shrine (new band name?) and grabbed scraps from the floor to compose some lifeless work for the job. But what else was I to do? Let go of what felt like my entire identity to make my shitty boss richer? No way, my dudes. Not this badass punk rock revolutionary, I was way too principled and tough for that.

Wake Up and Smell the Capitalism

At this point in my career, I have a pretty fair amount of freedom to pick and choose whose jobs I accept. It’s liberating, and it’s what brought me to work for BatesMeron. However, my professional successes in illustration are not without a word that art school left out of its back-patting curriculum: compromise.

In a conveniently rhetorical way, the question of how and when to sell your “style” is really not a question about style at all. It is a question of values versus goals and a question of short- versus long-term perspectives. In thinking about goals, we can decide what really matters to us and how we can get there. Is your goal to be a regular New Yorker contributor? Join the club. But also consider what trajectory you would have to embark upon to achieve this. Decide what steps you need to take and keep an open mind about where to put your work. Realistically, your editorial illustration for a somewhat problematic blog isn’t going to change the world for better or worse. It might piss off Twitter, but what doesn’t?

Many might think, “just abandon my ideals for a quick buck? No way!” Though I may sound like a defeatist, there’s another way to view it. You can use moments like this to re-examine and reinforce your values for where they can be more effectively represented in the future. Not every piece of the one-million-piece puzzle that makes up your career is going to be pretty. Sometimes it’s gonna be a weird grayish spot with an awkward cut. But you can always remember that, with enough pieces, it’ll eventually become the painting of dogs playing poker you saw on the front of the box when you started.

Now, what if you say, “Okay, that idealistic hippy crap is not my bag. My style needs to be preserved because it’s an extension of myself! Compromise is not in the cards, bucko!”

Fair enough! But consider this: Think about the person you were five years ago. Now eight years ago. Now ten. Can you say you have remained the same person that whole time? I sure hope not. Look at it this way, relentlessly preserving your own style is a recipe for stagnation. So many artists get away with making countless re-imaginings of the same work for years and, in a lot of cases, that’s just fine. But that is not to say there is no value in allowing yourself to grow. Use opportunities from clients as a way of experimenting with your style and allowing yourself to sit in the discomfort of trying something new.

Boil it Down

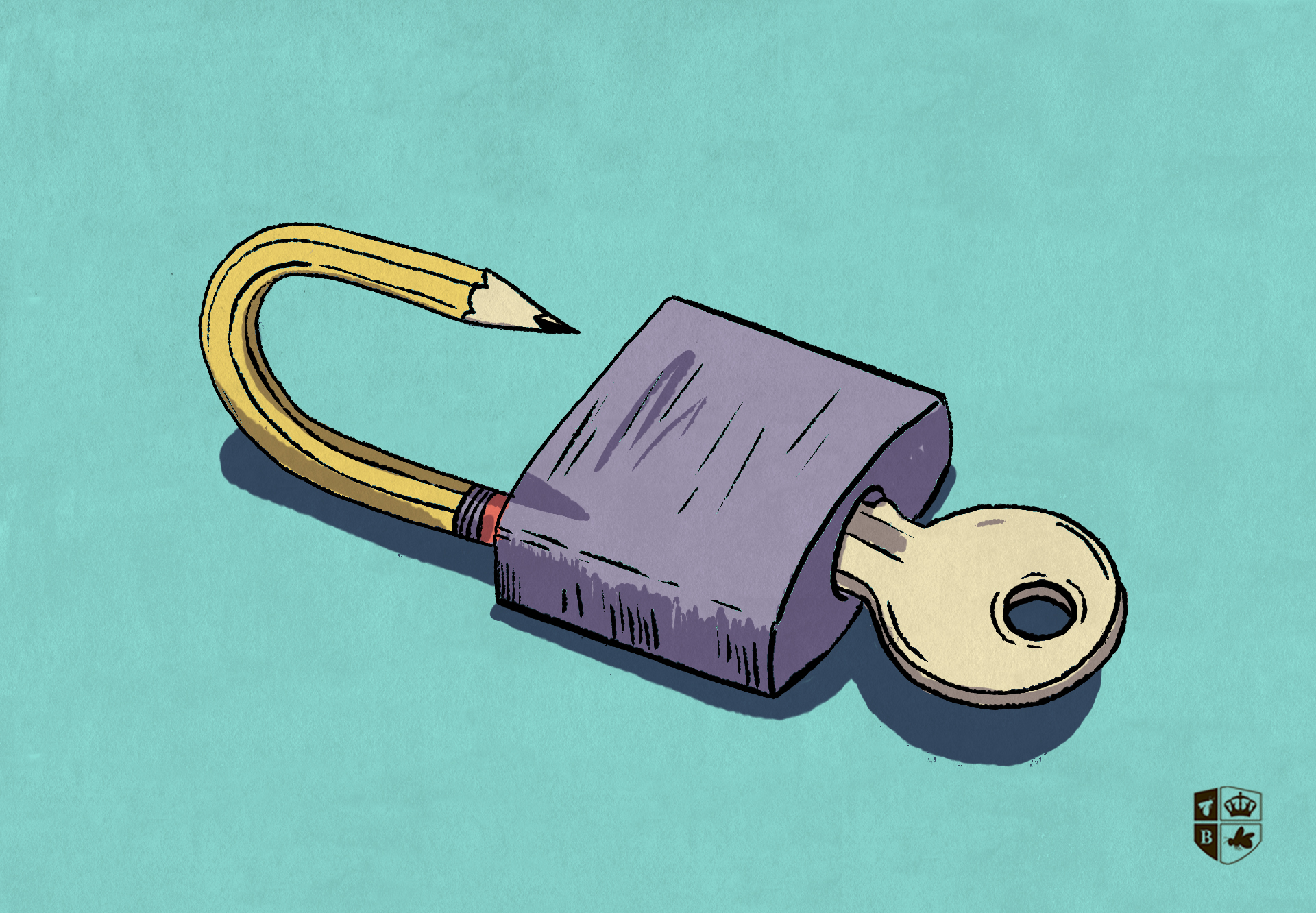

I hate speaking in platitudes, but this is the real deal. Every job you perform is an opportunity to grow and evolve, no matter how much it sucks. By approaching all your work with passion, you are actually paying respect to your style by using it in ways you never would have before. There’s inherent value in that. Even in the extreme scenario of licensing your style for someone’s brand, it doesn’t mean you have let go or sold out. You are and will forever be the only person who can do what you do. This is where that art school ego holds some water; Your work will always be yours and no cringey client can take that from you.

Thank you for coming to my TED talk.

Okay, but seriously, your choice to be an artist is not without its notes of narcissism and self-importance. That is not to say that the sanctity of your style isn’t real. It deserves to be treated with respect, but also with an open mind. We don’t make art because we want an easy life. We don’t make art because we’re emotionally stable. Being an artist is a twisted, beautiful, torturous, liberating, romantic, emotional nightmare. That’s real. However, in acknowledging all of this, you can give a little bit of yourself to get a lot more in the end. Open up that brain shrine and reach for those poker dogs. Your career trajectory can be a wild and interesting ride if you allow it to be. And it can also pay your bills.

Inspiration Information: 5 Blogs for Creatives

Punny or Not: Your Dad Joke Survival List

Six Questions for Amy Clardy