Avoiding Dark Patterns

In a previous blog, I wrote about the way in which website design intentionally creates a sense of trust so that users can feel at ease in providing personal information. Consequently, we have seen a rise of new and acceptable web pages that would otherwise seem taboo.

Information gathering has become an additional source of income for many new online companies. It’s done so by being able to leverage user information to add value to targeted ads or simply selling the information to marketing companies.

The more I study user experience (UX) or read into human interaction with electronics, the more I’ve been noticing a trend in websites: tricking users into taking an action which might not be in the user’s best interests. As UI/UX designers, we should always remember that with great power (knowledge) comes great responsibility. This fine line for designers lies between creating something in the interest of users (honest UI) and designing sites for a company’s interest—a deceitful practice known as dark patterns

I first learned about dark patterns during the 2015 LinkedIn lawsuit over the “Add Connection” feature. This feature gave LinkedIn permission to scrape contacts from your email and send out multiple emails to your contacts reminding them to join your personal network. As expected, people were not very happy with LinkedIn sending out emails on their behalf. While this was one of the major dark patterns to make headlines, there are many other examples seen throughout popular sites. In fact, one of my hobbies is to take note of such examples.

Here is a list of some of the clever dark pattern examples I’ve found that might not be noticeable at first glance:

Privacy Zuckering

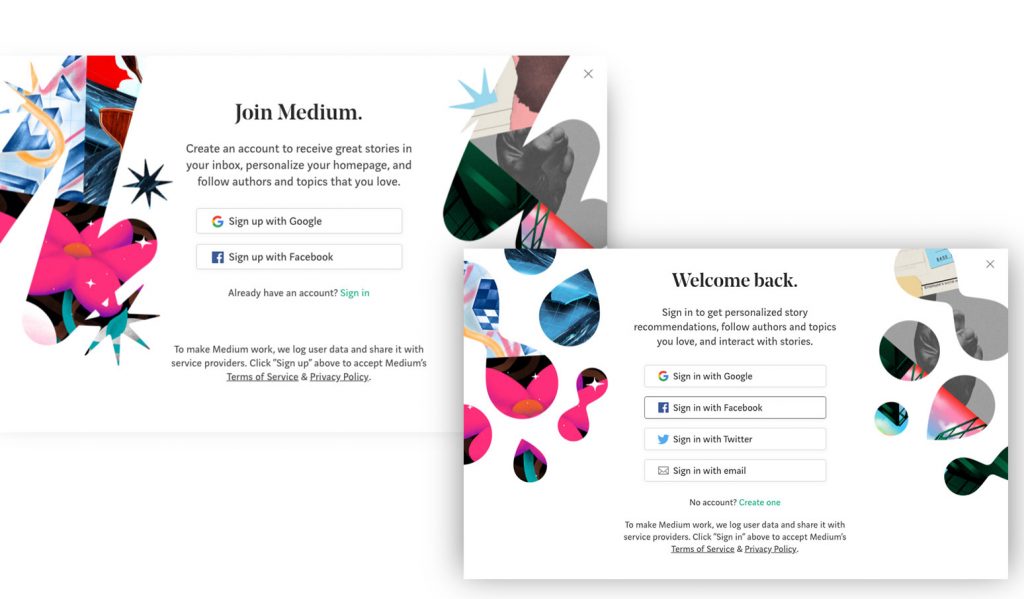

Named after Mark Zuckerberg, this term refers to instances when you are forced to provide more information than actually required. A lot of the time, users don’t even know they are doing this. A recent example that I ran into was on medium.com.

This website’s sign-up page seems to offer only one option for creating an account—and that requires using your Facebook or Google login. What you can’t immediately see is that a hidden email sign-up option is available, but only found after going through the sign-in link. By signing in with Facebook or Google, the medium.com is able to gather more of your information such as name, age, gender, location and so much more. The dangerous part about this is that most users do not know this is happening since it is all occurring behind the scenes. (ex: Medium.com)

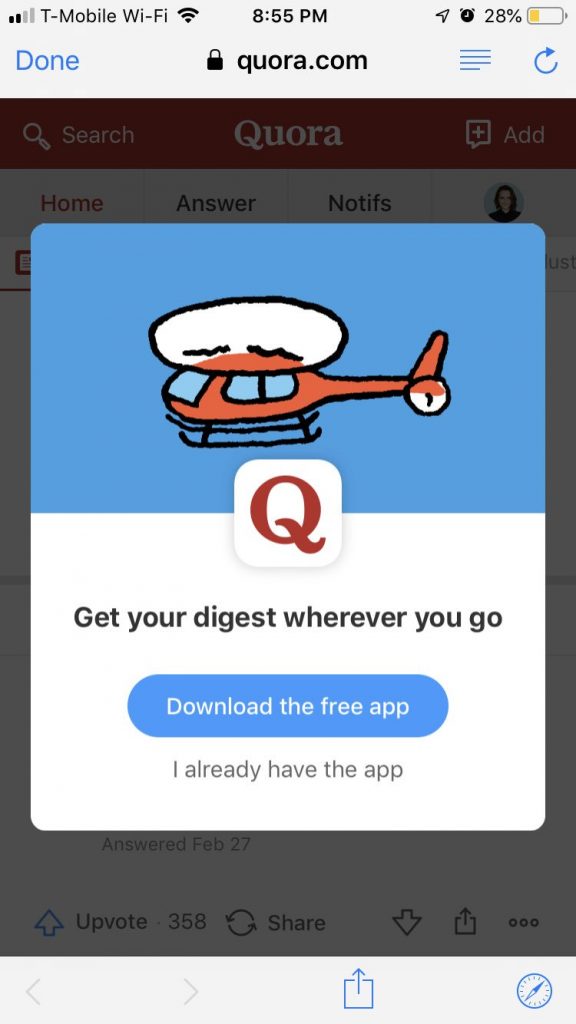

Mobile Forced Actions

A similar pattern is becoming evident in mobile apps. There are a few instances were mobile apps or mobile websites include pop-ups with no clear option for closing them out. Instead, to get rid of the pop-up, the user is forced to click on the sponsored links. (ex: Quora.com)

Mobile Hidden Actions

Another less obvious approach has also been used on mobile forms. Typically, mobile forms include opt-out content that is placed further down the page. This setup is done to guide the user away from the selection.

Misdirection

Lastly, as designers, we are aware that filled-in, colored selection boxes are more likely to be clicked if seen against an outlined selection box. This trick can be used to lead the user to click on a selection that benefits the company. It could mean the difference between “subscribing” and “unsubscribing” from a page.

Unfortunately, dark patterns have evolved and will continue to evolve. With every study on user behaviors, we are able to understand how to influence the way they interact on a webpage. That makes it our job as designers to be aware of our influence and use it wisely. It also makes it our job as consumers to combat dark patterns by staying informed on how UX has tricked users in the past and using that knowledge to understand where things are headed in the future.

Is Your Website An Accurate Reflection Of Your Brand Identity?

Targeted Ads: Friend or Foe?

Keeping Up with Culture